In the middle of a thick wood, an icy stream splashes down an artificial waterfall. Who would build a waterfall in the middle of nowhere?

Geography has stories to tell.

That is the truth at the center of worldbuilding by map. Map a galaxy or a city block: stories appear at every level. Stuck for ideas? Open a map, pick a spot at random, and ask, “What could happen here?”

I imagine Jules Verne, looking for an idea for another adventure. He pulls out an atlas. Wandering out into the Pacific, he spots a speck, a tiny reef marked “Tabor Island”. Idly, he traces the line of latitude eastward, crossing South America, Australia, and New Zealand. What a story it would be if a group of adventurers were to make that journey…Some time later, In Search of the Castaways is published.

In worldbuilding by map, as with bottom-up worldbuilding, it’s a good goal to keep going until you’ve found one or two stories. Then, stop. Focus on the stories. Add a few stray hooks and leave the rest of the setting a bit fuzzy. Later, you can pick up the hooks and flesh out the details in future stories, making it look like you meant to do that all along.

Worldbuilding by map requires some top-down decision making. Your decisions of genre, era, and type of story affect the maps you’ll want to create or find. If you want to tell a story of an undersea race to a treasure, then the map of a fifteenth-century walled city won’t be very helpful. However, if you want to design a sprawling space station, that same walled city might, oddly enough, give you some interesting ideas for your station’s layout.

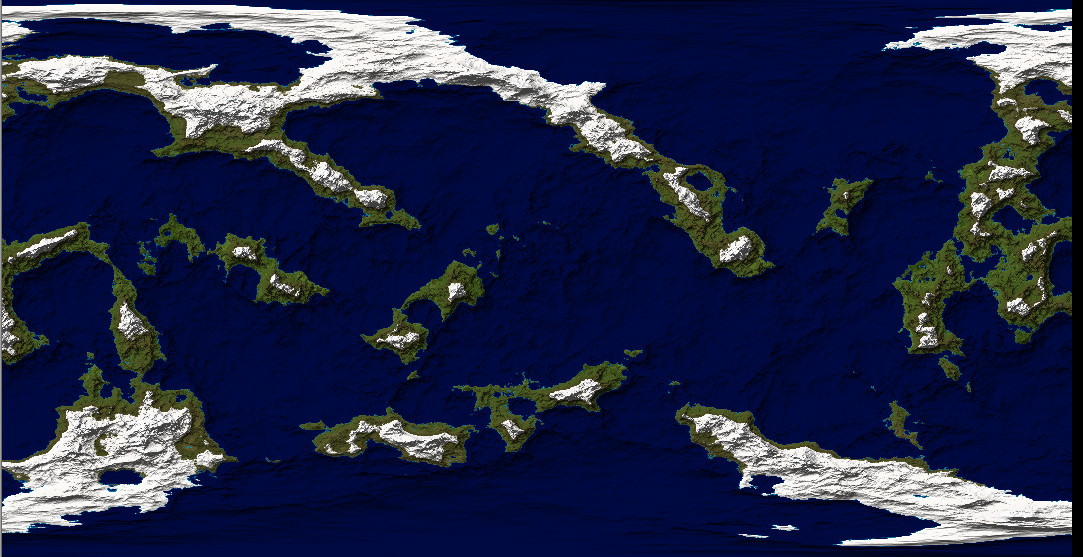

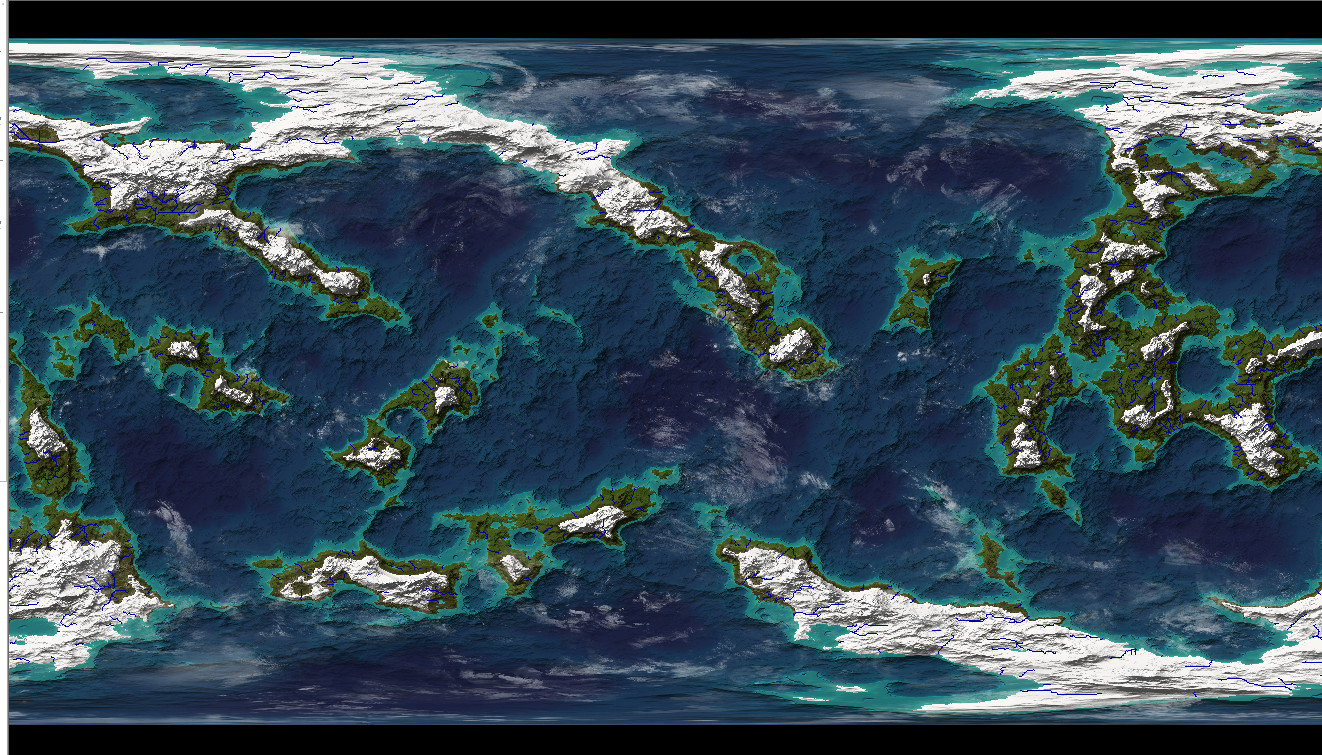

I happen to own a copy of Profantasy Software’s “Fractal Terrains 3+” program and I will snatch at any excuse to use it. So, when we started talking about worldbuilding by map, I opened the program. Our idea was to generate three different planets and see which one, if any, had geography that stood out as being particularly intriguing or amusing or otherwise worthy of story. Thus, we were creating our own map, and that map was on a planetary scale. Therefore, the stories we were most likely to find would probably be somewhere on a country-to-continent scale.

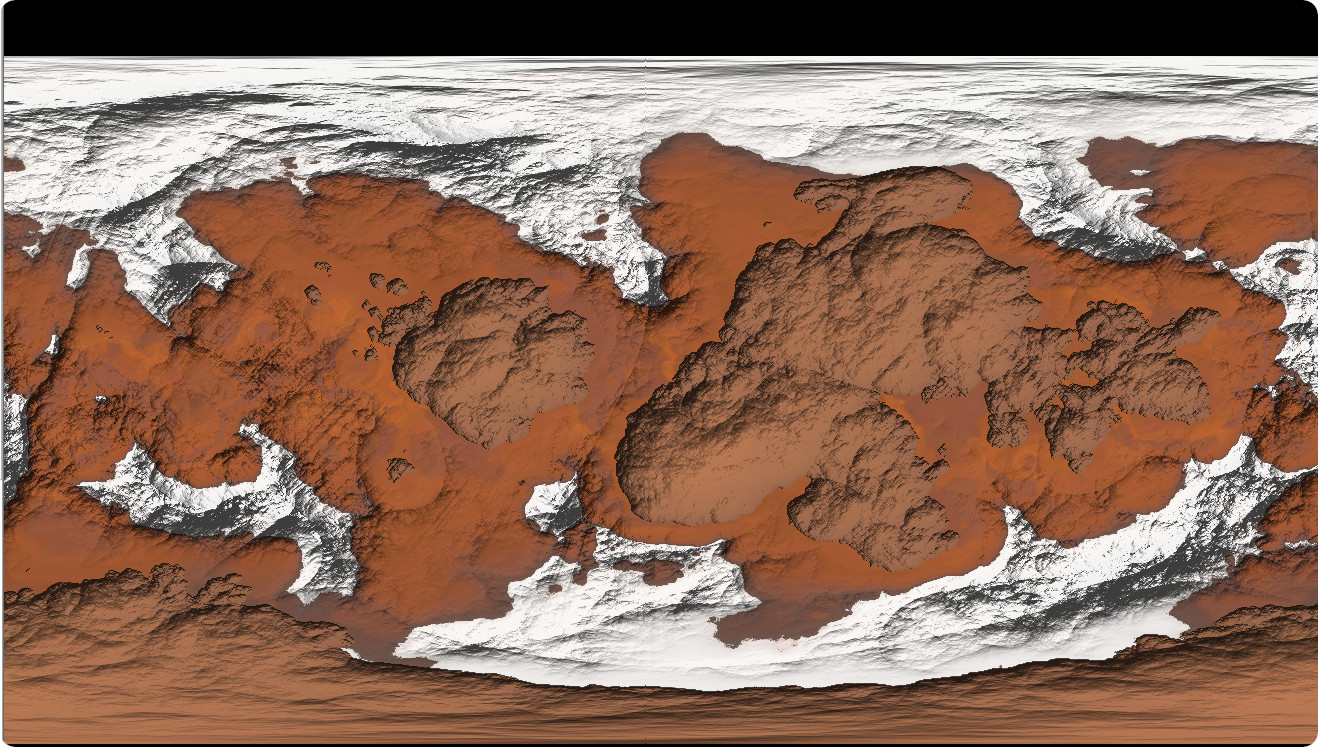

We created maps of three planets: one Earth-like, one Mars-like, and one gas giant. The gas giant was frankly dull—hardly surprising. I can imagine stories taking place in orbit around a gas giant, and high in the atmosphere, but a gas giant’s “geography” is really more of a “general atmospheric circulation model” which is not Fractal Terrains’ area of expertise. Move on.

We took a planet with Mars-like size, gave it an atmosphere, dropped the incoming radiation in an effort to reduce atmospheric sputter, and tuned up the greenhouse effect. Hot! Much too hot Uninhabitably hot! We fiddled around until we had something vaguely inhabitable but we didn’t find any stories jumping out at us.

This planet has Mars-like characteristics but don’t trust it

The Earth-like planet, on the other hand, had geography that looked out and spoke to us. I use the phrase “looked out” advisedly, for we found ourselves staring at a dragon.

We would like to thank pareodelia for its invaluable help in this worldbuilding exercise

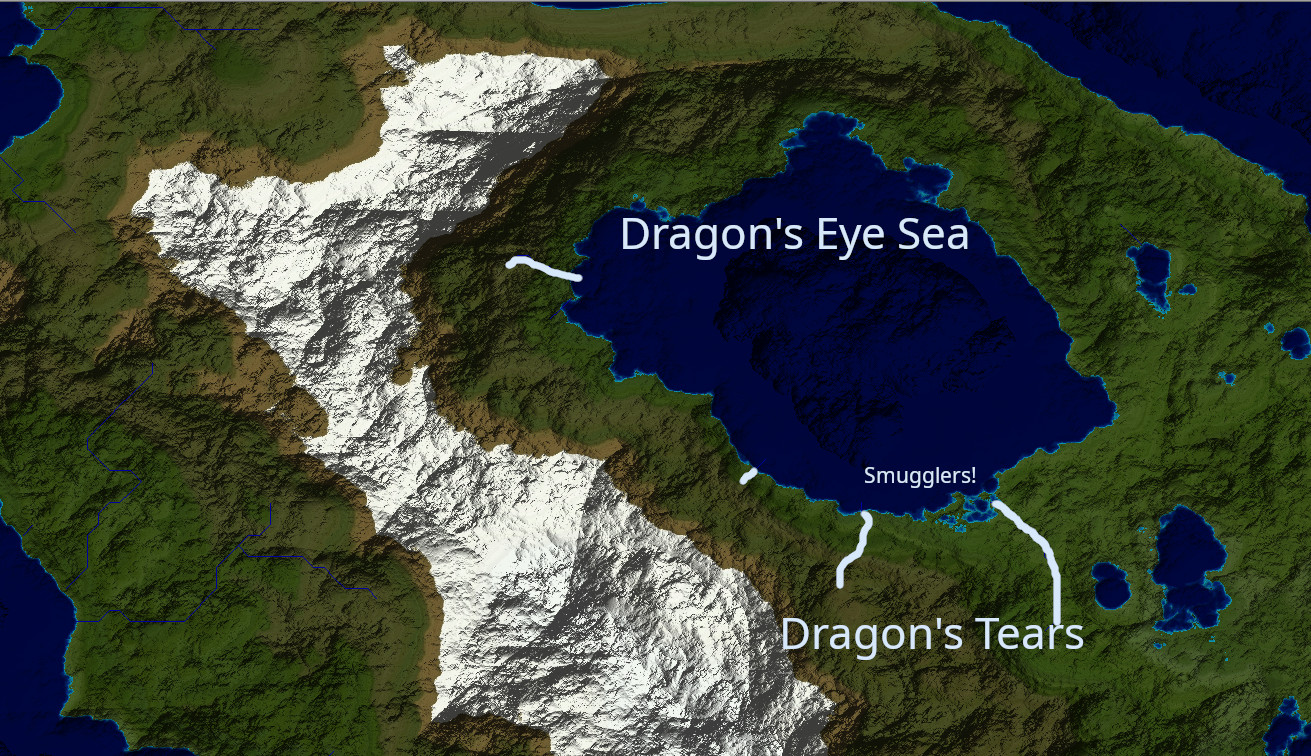

Instantly, the giant eye was named, “Dragon’s Eye Sea.” We discarded the other maps and focused on the Dragon’s Eye Sea section of this world. The upshot of our world-creating exercise was one world with Earth-like gravity, size, axial tilt, and climate, plenty of oceans, and several large land masses.

On to the geography! In naming one area the “Dragon’s Eye Sea”, we have created a culture which has a concept of dragon. When I pointed this out to my partner, his response was, “Everyone has a concept of dragon. The sentient crabs of Celephus IV have a concept of dragon. We’re fine.” So, there we are. We’ve also created a civilization with enough grasp of cartography to be aware of their region’s general appearance, but that’s just a good story hook.

The Dragon’s Eye Sea has a maximum depth of over 6000 ft and an area of around 400,000 square kilometers. The Black Sea on Earth is a bit larger and a bit deeper but it can give us a sense of scale. From a story perspective, the Black Sea is huge! It’s bordered by six countries with a stack of islands, a fascinating ecosystem, a long list of ports and resorts, and enough history to fill a bookcase.

The Dragon’s Eye Sea. Pale highlights mark the courses of the sea’s largest tributary rivers

Turning back to our map, a few quick clicks generated a set of rivers across the world, including several that run into the Dragon’s Eye Sea. I named the three rivers along the bottom the “Dragon’s Tears”, though each one would have its own name, of course. We’ve got some high mountains (peak heights ranging from 10 000 ft to 26 000 ft) westward of the sea. How would they affect the weather? My partner suggested that the prevailing winds would travel west-to-east, giving the west side of the dragon’s head a moist climate and leaving the Dragon’s Eye Sea in the rain shadow. That, in turn, suggests that the rivers and other freshwater sources will be particularly valuable resources and probably heavily settled. There’s flatter land on the south-east border with a large river running through it—probably excellent for agriculture. The steep slopes on the north-west side might make good grape country, suggesting a major exporter of wine and associated products. Perhaps the mountains are rich in ores, or valuable woods, or even highly-prized edible mushrooms. In the south, just west of the longest of the Dragon’s Tear’s rivers, is a nest of shallow waters and islands. This fascinating geography just shouts “Smugglers!”

Without stopping to think, we’ve generated a short stack of cultures and their stories. Truffle hunters face a terrible woodland foe; smugglers snap their fingers at revenue agents; the wine country and grain country struggle to reach a trade agreement that both sides will accept.

At that point, the question arose, “How does this region communicate with anyone?” It’s a good question—we can’t see any rivers running down to the sea from the northern heights (about 6000 feet high). The western mountain chain might be impassible. Looking west and north of the Dragon’s Eye Sea, we see a fine gulf, which my partner immediately names “the Dragon’s Gullet.” We can imagine adventurers walking east from the Dragon’s Gullet, following the east-west river, and then skirting the lower slopes of the western mountains, eventually heading over the northern heights to the Dragon’s Eye Sea. We could also imagine ships leaving port at Dragon’s Gullet to sail completely around the dragon’s snout and up to a northern port, and again over some northern pass. That northern pass is becoming increasingly valuable as a channel of communication: an excellent spot for all manner of stories. Bold riders, stealthy spies, hardy merchants, innocent tourists…anyone could be out there. And all of them eventually land in one city. Is it walled, or even hewn from the mountain itself? Fascinating.

Before I can get too far into designing my bottleneck city, my partner speaks up. “You know what would be interesting? Flip the script.”

Keep in mind, I have at least seven scripts metaphorically scattered around at this point. “Flip which script?”

“The script of colonization. What if we set this entire region at the edge of the age of exploration? The seacoast cultures are just ready to start looking beyond their own local borders when an undiscovered undersea civilization rises from the deep and begins exploring them. It could give players a feeling of empathy for invaded cultures. It’s reasonable. That sea is deep enough to hold anything.” Very true. In the open ocean, six thousand feet deep is well into the bathypelagic or ‘midnight’ zone. That’s a rich line of stories with space for adventure, diplomacy, intrigue, knavery, individual heroism and collective action. It will take some careful thought and could be quite rewarding.

Let’s grab a map and go tell some stories.

The maps used in this exercise were created by H. Osborne using ProFantasy’s Fractal Terrains 3+ and Bill Roach’s Terraformer 0.5

0 Comments